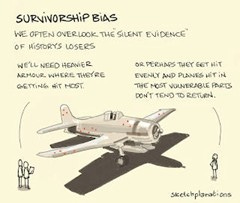

While fighting the Second World War, the British Royal Air Force (RAF) ended up with a very strange problem. It needed to attach heavy plating to its fighter jets to protect them from gunfire from the German fighter planes and their anti-aircraft guns. The trouble was that, since the plating was heavy, it had to be used sparingly at the right points of the aircraft, where the Germans were most likely to attack.

Jordan Ellenberg writes about this in a great book titled How Not to Be Wrong: The Hidden Maths of Everyday Life: “The damage [of the German bullets] wasn’t uniformly distributed across the [British] aircraft. There were more bullet holes in the fuselage, not so many in the engines.”

What did this data suggest? It suggested that the chances of the plane’s fuselage being attacked were higher, and that was the part of the plane that seemed to be the most vulnerable.

QED.

One guy – a statistician called Abraham Wald, disagreed and, to their credit, the RAF blokes who took the decisions on these things, decided to hear him out. Tim Harford, whose writing I find most interesting (The Undercover Economist is a must-read if you are not an economist. If you are an economist, it is a must, must read) wrote about Wald’s response in How to Make the World Add Up: “Wald’s written response was highly technical, but the key idea is this: we only observe damage in the planes that return. What about the planes that were shot down?”

The ones that didn’t come back!

This data wasn’t available to the British RAF. Back to Ellenberg, he writes: “The armour, said Wald, doesn’t go where bullet holes are. It goes where bullet holes aren’t: on the engines. Wald’s insight was simply to ask: where are the missing holes? The ones that would have been all over the engine casing if the damage had been spread equally all over the plane. The missing bullet holes were on the missing planes. The reason planes were coming back with fewer hits to the engine is that planes that got hit in the engine weren’t coming back.” They crashed.

And then the change was made - the planes were plated around the engine and not the fuselage as the data had originally suggested.

The original data in the British case had a bias built into it that is now called the survivorship bias. It captured the bullet patterns of only those planes that survived, that made it back to the air force base and not every British plane that got hit by a German bullet.

Ellenberg explains this in another way: “If you go the recovery room at the hospital, you’ll see a lot more people with bullet holes in their legs than people with bullet holes in their chests. But that’s not because people don’t get shot in the chest; it’s because the people who get shot in the chest don’t recover.”

When someone - say, a smoker - defends the habit by giving you an example of an eighty-year-old who smokes six cigarettes every day and has a lung of a fifteen-year-old…...well, that is survivorship bias at work (it’s more than that, it’s outright lying, but we will let that pass). When insufferable people (and their fathers-in-law, who are generally equally insufferable) take examples of Steve Jobs and the rest of the start-up stars line-up as examples of why you need to take risks, there we go again. And, if you want to know about the success of day-trading in stocks, it is 7 to 20%, so tell that to the one who wants you to join in on the bonanza-in-the-offing.

The way to eliminate the bias: for every plane that returned, count one that did not, ask what is missing. Look for trends, not just extreme successes.

Isn’t this even truer today, because of the dubious quality of what we read and hear?